Fighting for Reef Fish

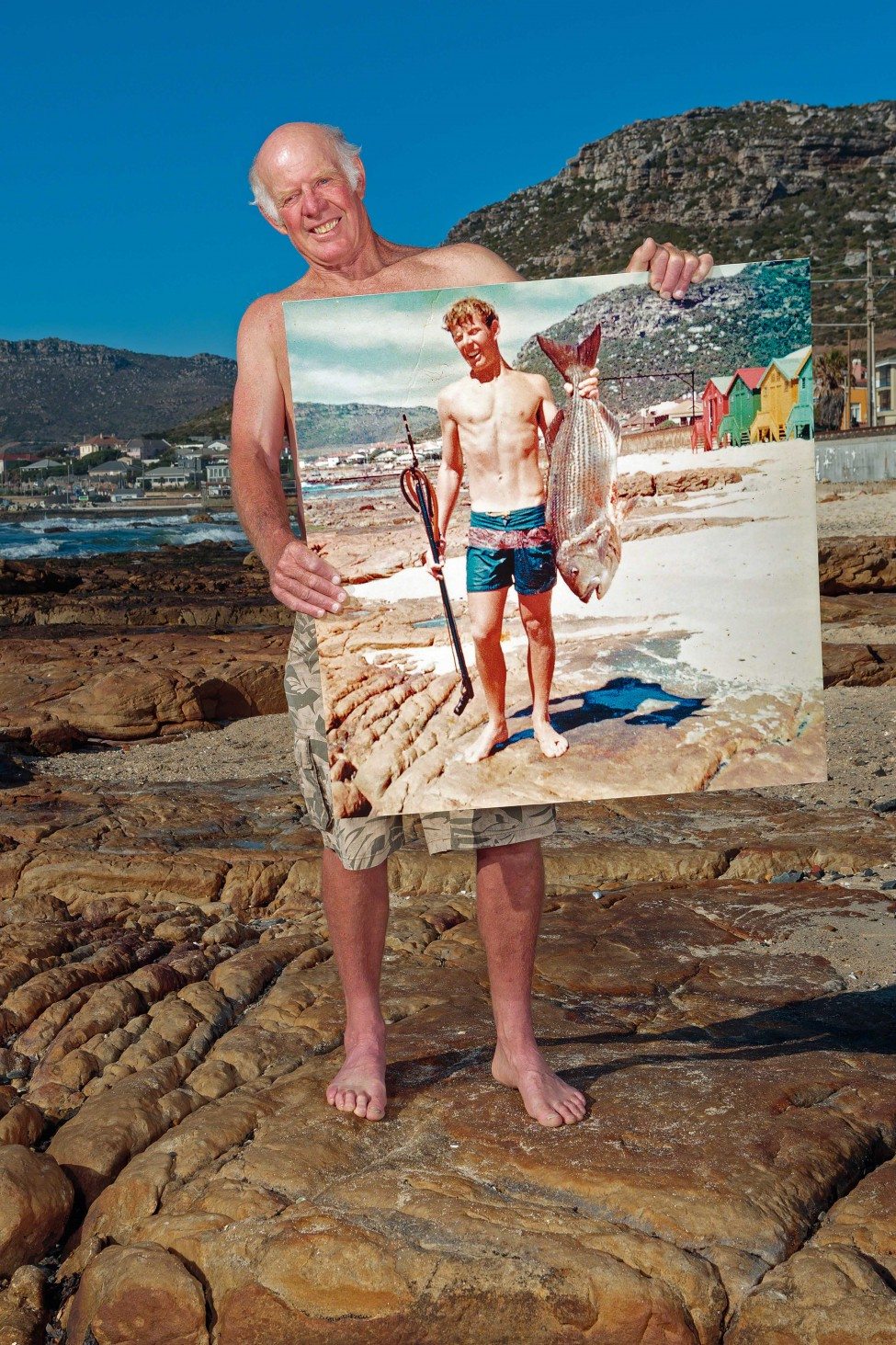

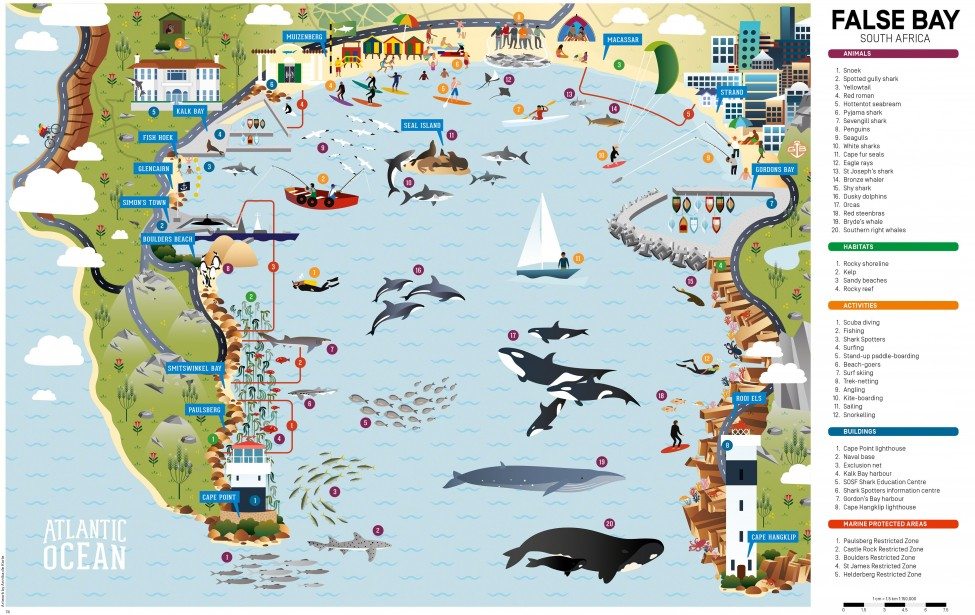

In False Bay, South Africa, Philippa Ehrlich learns that protecting the area’s critically endangered reef fish species is going to require people – often with different needs and agendas – to collaborate.

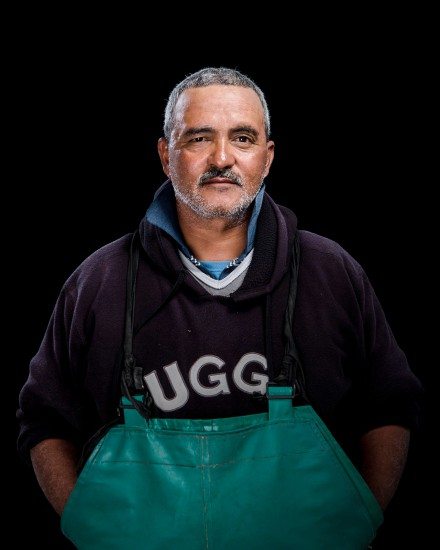

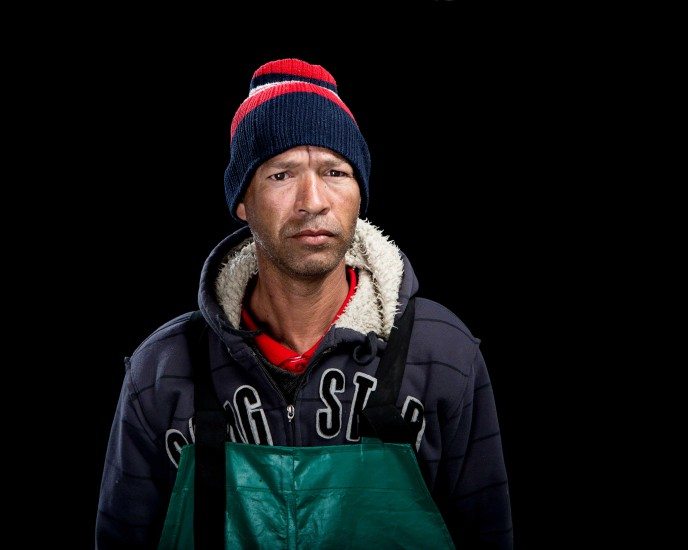

I pull my face deeper into the hood of my green oilskin and shudder against the icy wind. We are now into our second hour aboard the Blue Starfish and are halfway to the mouth of False Bay. It is still pitch dark and in the distance a dim horseshoe of twinkles indicates where the ocean meets the land, reminding me of how vulnerable we are as we slough through this deep, inky bay of invisible life. This is a journey that traditional hand-line fishermen have been making for generations, but it is uncertain how much longer they will be able to continue. South Africa’s commercially important line-fishes have been reduced to 10% of past levels. Specifically, popu-lations of bottom-living reef species, which make up 25% of the country’s commercial fish stocks, have collapsed.

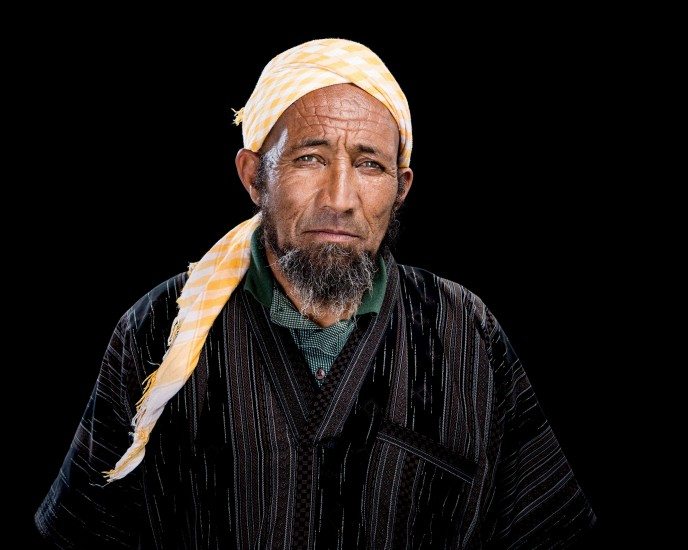

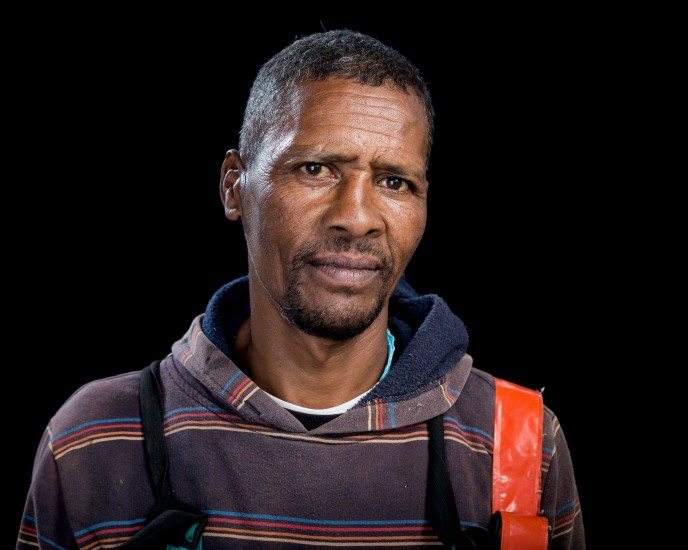

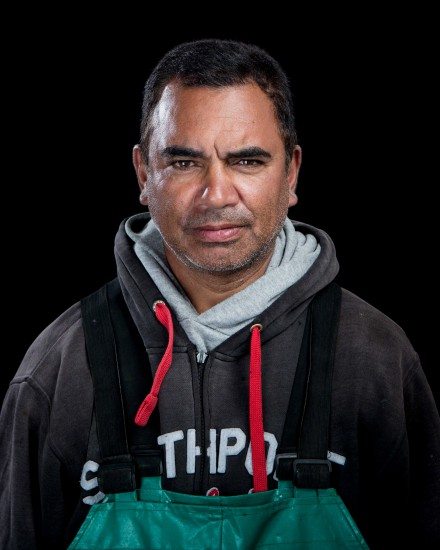

‘My darling, you’re shivering. Turn to face the back of the boat.’ I am startled by an old fisherman who is sitting just to my right. Most of the crew are playing cards at the back of the boat or sleeping on the bunks below. The old man’s name is Yussuf*. He is not one of the crew, but used to skipper his own boat and, despite being in his 70s, he cannot bear to be away from the sea. ‘You know, Cape Town has always been a fishing place,’ he explains. ‘The pioneers of fishing were the Muslim people. Some of them were runaway slaves and some were freed slaves. When they became free they became fishermen.’

False Bay, also known as ‘die blou dam’ (the blue dam) to local communities, is a microcosm for what has happened in the rest of South Africa and in other parts of the world. A hundred years ago the bay teemed with life, and fish and fishermen thrived. Then came decades of concentrated exploitation that has decimated fish stocks. And yet, despite shrinking catches and increasing costs, the communities whose culture and livelihood were founded on fishing are still desperately clutching their lines.

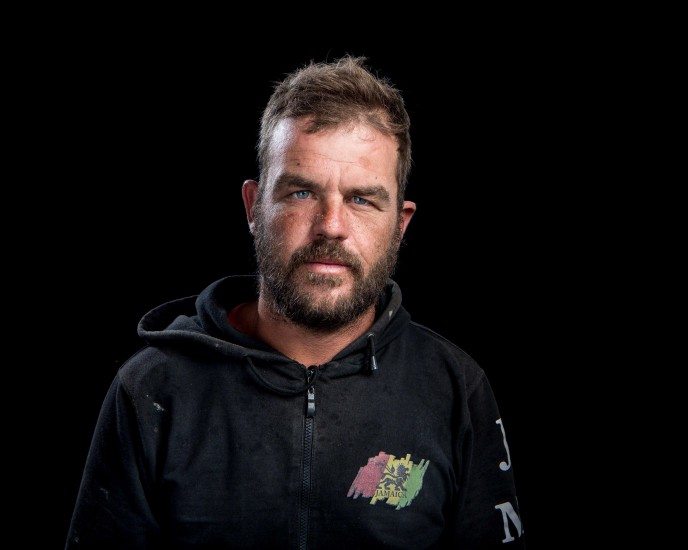

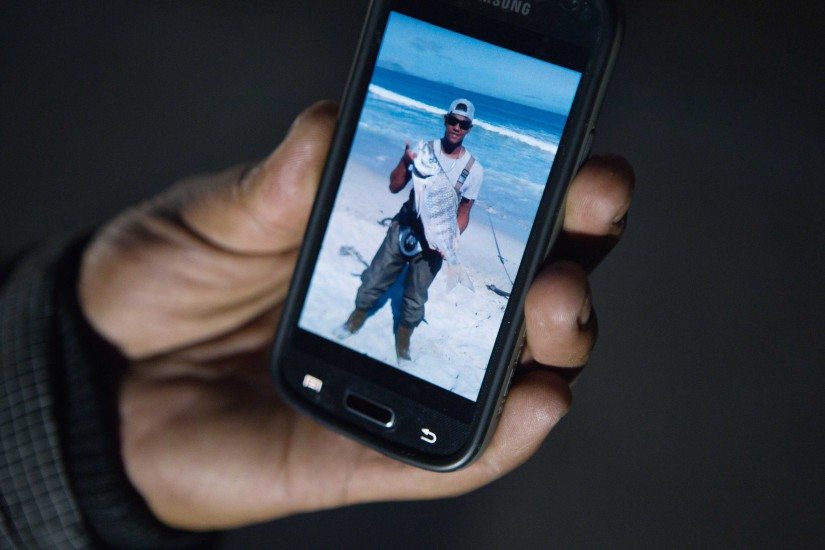

As the sun creeps up over the eastern edge of False Bay, we reach the mouth and anchor in the shadow of a series of arrow-shaped peaks. About 16 other vessels surround us. Jacob Saunders*, the most experienced fisherman on the boat, is talking excitedly while he prepares his fishing gear. ‘When the fish start to bite, it puts the adrenalin right in you and you want to catch another one and another one.’ He throws in his line and almost immediately pulls in a large, shiny fish with long, razor-sharp teeth – a snoek Thyrsites atun. He grips the powerful fish under his arm and snaps its neck. Macabrely captivating as it might be, I am not here to learn about the fast-growing and migratory snoek. I am after one of the bay’s permanent and grander residents.

SOSF Marine Conservation Photography Grant

The Save Our Seas Foundation believes that photography is a powerful tool for marine conservation. We invite emerging conservation and wildlife photographers who have a passion for marine subjects to apply for our 2016 grant. This is a unique opportunity for photographers to go on assignment, earn an income and gain experience under the guidance of National Geographic photographer Thomas Peschak.