Connecting consumers with conservation

Do you check the source of your imported Ugandan coffee? And avoid products made with palm oil because you know what that means for orang-utan habitat in Borneo? Tracing the impact of your purchases is tricky, particularly when so many products are integral to our daily lives and the components of most of them are difficult to track. Like that sweater you bought, or an upgraded smartphone you need for work. New maps published this year in the science journal Nature Ecology & Evolution trace the products you buy to their impact on threatened species in other countries. The idea is to connect consumers with the actual impact their purchases have on conservation, so that we can take smarter steps to protect biodiversity.

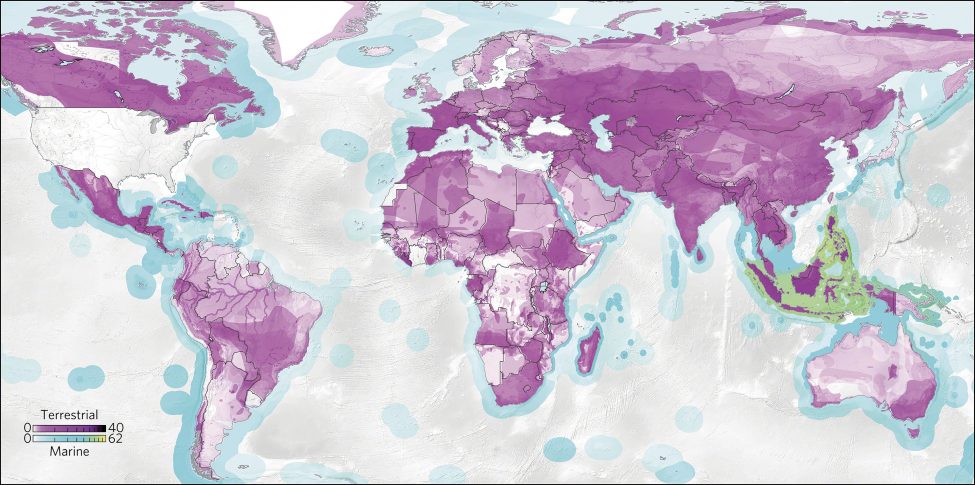

Daniel Moran at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim and Keiichiro Kanemoto at Shinshu University in Matsumoto in Japan analysed 6,803 threatened species worldwide – species listed as Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. They then looked at the different products whose manufacture or sale places those species at risk. They traced the products to their final consumers in 187 countries. By laying global supply-chain information over the species-threat information, we can visualise the actual effects of trade. The result? Maps that show which countries and which products threaten species in the remaining biodiversity hotspots on earth.