Sharks and Rays at CMS COP11

CMS COP11, held in Quito, Ecuador, towards the end of 2014, listed a record number of migratory sharks and rays for global protection. But, asks Andrea Pauly, what comes next?

Photo by Michael Scholl

After six days of intense negotiations, the 11th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS COP11) marked a new era in international elasmobranch conservation.

‘The conference in Quito has generated an unprecedented level of attention for migratory sharks and rays,’ commented Bradnee Chambers, the Convention’s executive secretary. ‘Never before in the 35-year history of CMS has the international community agreed to list as many species of elasmobranchs in the Appendices of the Convention. This highlights the growing commitment of the 120 member states to conserve these species.’

A record number of 21 proposals to list shark and ray species was approved (see table on page 115), as was Resolution 11.20 on the Conservation of Migratory Shark and Rays, which addresses the most pressing threats to these fishes and provides guidance for Parties on the priority actions that need to be taken in the coming years. In some circles, COP11 has been labelled the Shark COP, raising expectations for the future performance of the Convention to improve the conservation status of these species.

Photo by Michael Scholl

Shark conservation under CMS

As a treaty under the aegis of the United Nations Environment Programme, CMS offers a global platform for the conservation and sustainable use of migratory animals and their habitats. It also lays the legal foundation for internationally coordinated conservation measures throughout their range. As the only global Convention specialising in the conservation of migratory species, CMS complements a number of other wildlife-related Conventions.

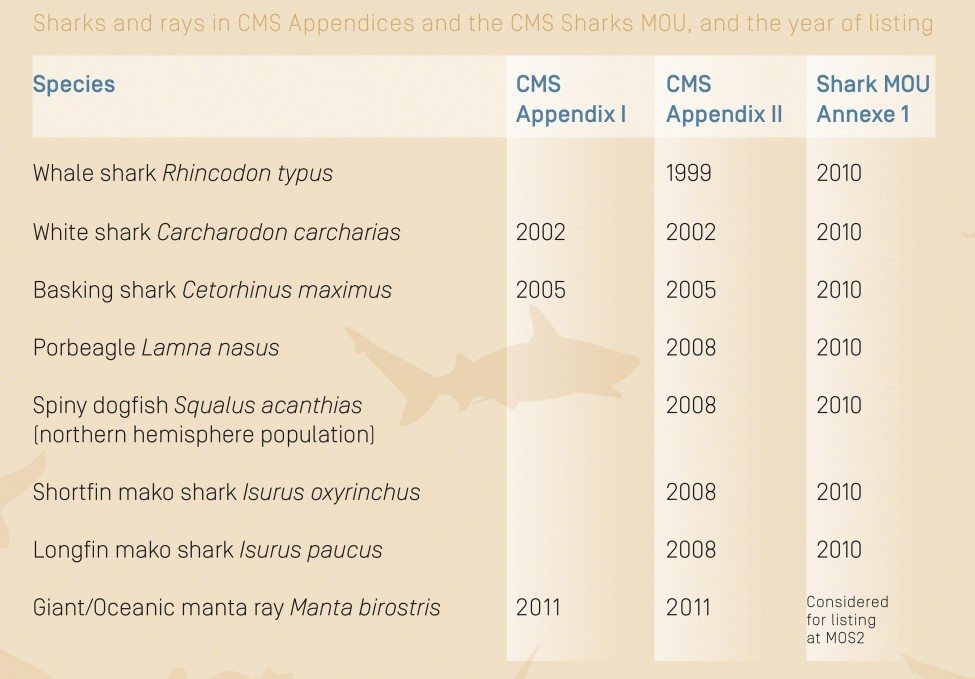

CMS has a long history of shark conservation, starting with the listing of the whale shark in 1999. This was before any Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) or the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) had agreed to manage any elasmobranch species. Between 2002 and 2011 five more shark species were listed under CMS, including the first commercially exploited species in Appendix II: the shortfin mako and porbeagle sharks. In 2005, at COP8, CMS Parties called upon range States to develop a global instrument for the protection of migratory sharks. Hence, some see the Convention as breaking new ground for conservation initiatives, providing a suitable forum to bring species onto the international agenda.

In response to the 2005 call for a global instrument, and after three rounds of negotiations, the CMS Memorandum of Understanding for migratory sharks (the Sharks MOU) was agreed in 2010. The Sharks MOU represents the first global agreement dedicated to the conservation of migratory sharks and rays. When it was adopted, the negotiating Parties agreed that it should be legally non-binding and should aim to achieve and maintain a favourable conservation status for migratory sharks. This should be based on the best available scientific information and take into account the socio-economic value of these species.

As of February 2015, 38 countries have signed this agreement, thereby committing themselves to implementing the associated global Conservation Plan for Sharks. The main objectives of the Plan (see box on page 114) focus on five core areas that relate to research and data collection, fisheries management, habitat protection, raising awareness and international cooperation.

COP11

The COP11 decision to list no fewer than 21 additional shark and ray species represents a remarkable moment in the history of CMS. Proposed by Kenya, Egypt, the European Union, Fiji, Costa Rica and Ecuador, the additions comprised six shark species (three thresher sharks, silky shark, great hammerhead and scalloped hammerhead) and 15 rays (the sawfishes, devil rays and reef manta ray). All 120 Parties agreed that these species require international protection, and in some cases even strict protection.

As of February 2015, when the COP11 listings came into force, the Convention counts 29 species of sharks and rays in its two Appendices (see table on page 114). Sixteen ray species (manta rays, devil rays and sawfishes) and two shark species (white and basking sharks) are listed in Appendix I and Appendix II, while an additional 11 shark species are contained only in Appendix II.

The species listed in Appendix I – the highest protection category of the Convention – are those that are threatened with extinction (see box on page 114). Appendix I foresees strict protection measures, including a ban on catching the listed species (as defined in Article 5 of the CMS). Parties that are range States for these species are legally bound to incorporate the strict protection measures into their national laws and to ensure that the Convention’s provisions are fully enforced.

Migratory species that need, or would significantly benefit from, international cooperation are listed in Appendix II of the CMS. An Appendix II listing commits countries to coordinating transboundary conservation measures throughout the species’ range by developing a specialised agreement (the Sharks MOU).

Resolution 11.20 on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks and Rays, which was also approved at the COP11 meeting, makes provision for sustainable fishing and trade, the enforcement of the ban on finning, compliance with regulations under RFMOs and CITES relating to sharks and rays, and the development and implementation of national plans of action for sharks based on the International Plan of Action of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The resolution does not intend to duplicate the work of the Sharks MOU, although it contains certain key elements of the MOU and the Conservation Plan for Migratory Sharks. Rather, it was developed to complement and support the objectives of the MOU by utilising the strength of the Convention’s broad membership.

SOSF and CMS

Words by Sarah Fowler

It is no coincidence that many of the species listed in the Appendices of CMS have also been the subject of numerous SOSF research projects. The ‘big three’ species (the whale, white and basking sharks) that were the first sharks to be listed under CMS have an almost equally long history of SOSF-funded research. More recently, the SOSF has paid particular attention to research and conservation initiatives that focus on the poorly known but highly endangered sawfishes, Pristidae, and the mantas and devil rays, and has issued calls for research and conservation projects dedicated to these species. Not only new data, but also increased scientific and public awareness of the risks faced by these rays emerged from these SOSF initiatives, and together they contributed significantly to the development of the successful listing proposals in 2014. We look forward to continuing our support for the implementation of the listings through the efforts of SOSF researchers.

Next steps and challenges

The next important step after COP11 will be the Second Meeting of Signatories of the CMS Sharks MOU (MOS2), which is planned for early 2016. MOS2 will provide a forum for discussing whether species recently listed on CMS should be added to the MOU species list; currently only seven shark species are covered by the MOU. An important factor to be taken into account by the signatories is the capacity of this young agreement to conserve a long list of protected species for which individually defined measures must be undertaken.

A second crucial decision will be to agree on priorities as suggested by the MOU Advisory Committee and to organise implementation at the international level through cooperation with other range states and in conjunction with existing treaties, such as the FAO, CITES and RFMOs. Signatories have agreed that the activities of existing international organisations, in particular FAO, RFMOs and Regional Seas Conventions, should be complemented rather than duplicated. The mandate of RFMOs to promote the conservation and management of fish stocks is well recognised by the MOU signatories.

This need to feed the objectives of the Sharks MOU into the agendas of other international and regional organisations dealing with the conservation and management of migratory elasmobranchs is, in fact, both the greatest potential and the greatest challenge of the MOU. This is particularly true when it comes to one of the MOU’s main objectives: to make fisheries more sustainable. Here good cooperation with RFMOs is an absolute must. Ensuring that both directed and non-directed fisheries for sharks and rays are sustainable requires proper monitoring schemes so that data can be collected and information can be shared at the species level. The Convention’s broad membership is expected to bring expertise to global conservation efforts in areas such as research, compliance, enforcement and capacity building.

More developed is the relationship between CITES and CMS, whose Parties have agreed to a Joint Programme of Work. Parties to both Conventions have agreed to optimise the effectiveness of their actions concerning sharks and rays. They have requested their Secretariats to strengthen synergies with fisheries and other relevant bodies and to cooperate on building capacity so that the work of both Conventions can be carried out successfully.

Finally, NGOs and academic institutions are seen as important partners for the Sharks MOU. The CMS Secretariat has benefited from excellent cooperation with NGOs in the past when it comes to implementation. As mandated by its Parties, the CMS Secretariat has already built up a wide network of partners who actively support its efforts to build capacity, raise awareness and conduct research. The MOU offers the opportunity for relevant organisations to become official cooperating partners. At MOS2, signatories are expected to decide on the terms of reference for such partnerships and the role that partners to the MOU may play.

The decisions of COP11 have created strong political momentum for the conservation of sharks and rays around the world. The time is right to strengthen political will to implement the provisions of the CMS and to encourage more countries to sign the CMS Sharks MOU. Time will tell how feasible it is to bridge effectively the needs of fisheries and conservation.

For more information:

The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals: www.cms.int

Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks: www.sharksmou.org

CMS Species Appendices

- Appendix I: Migratory species threatened with extinction are listed in Appendix I, the highest protection category of the Convention. Countries that are party to the Convention strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that could endanger them.

- Appendix II: Appendix II includes migratory species that need or would significantly benefit from international cooperation. It commits countries to coordinating transboundary conservation measures throughout the species’ range by developing a specialised agreement. To this end, the CMS encourages range States to conclude global or regional agreements. In this respect, CMS acts as a framework Convention. The agreements in accordance with the provisions of Appendix II may range from legally binding treaties to less formal instruments, such as memoranda of understanding – the CMS Sharks MOU is an example – and these can be adapted to the requirements of particular regions. The capacity to develop models that are tailored to conservation needs across the migratory species’ range is unique to CMS.

Objectives of the CMS Conservation Plan

The objectives of the CMS Sharks MOU Conservation Plan are listed in its Annexe III:

- To improve the understanding of migratory shark populations through research, monitoring and information exchange.

- To ensure that directed and non-directed fisheries for sharks are sustainable.

- To ensure the protection of critical habitats and migratory corridors and critical life stages of sharks as far as is practicable.

- To increase public awareness of threats to sharks and their habitats and encourage public participation in conservation activities.

- To enhance national, regional and international cooperation. In pursuing activities described under this objective, signatories should endeavour to cooperate through RFMOs, the FAO, Regional Seas Conventions and multi-lateral environmental agreements related to biodiversity. Signatories to the CMS Sharks MOU

As of November 2014, the CMS Sharks MOU had 38 signatories: 37 national governments and the European Union.